Creating performant git commands.

Experiencing slow tooling? This article was originally written amid the growing pains of an increasingly large monorepo, where git commands could take 10s+ to execute. For developers that do a lot of context switching, and for a repo with many contributors — it adds up.

There are plenty of prefaces here. If you’re just looking for the improvements, feel free to scroll down to the “Ok so, how do I git gud?” section.

Ever seen a slow repo?

Tested on a fully-installed 5.9GB repo

1st try (git status)

It took 10.88 seconds to enumerate untracked files. 'status -uno'

may speed it up, but you have to be careful not to forget to add

new files yourself (see 'git help status').

nothing to commit, working tree clean

git status 0.45s user 2.25s system 24% cpu 11.109 total2nd try (git gc)

It took 6.87 seconds to...

git status 0.41s user 1.99s system 33% cpu 7.137 total3rd try (git gc —aggressive)

It took 3.55 seconds to...

git status 0.42s user 2.10s system 69% cpu 3.658 total4th try (git status -uno)

nothing to commit (use -u to show untracked files)

git status -uno 0.06s user 0.56s system 556% cpu 0.112 total5th try (fsmonitor-watchman)

nothing to commit, working tree clean

git status 0.31s user 1.02s system 92% cpu 1.435 totalA look at git fundamentals

git clone

O(n) where “n” includes every commit in history, which means it includes every file ever committed to the repository — even if currently deleted. It also includes every commit referenced by a branch, which could include additional files that don’t exist in the standard “clean” repo checkout.

These can be tuned with --depth and --branch, respectively. But these clone flags may only be useful in certain scenarios where the user does not need history and/or does not need to check out different branches.

git status

Actually runs git diff twice. Once to compare HEAD to staging area, another to compare staging to your work-tree.

According to official docs, git diff can use any of the four following algorithms: --diff-algorithm={patience|minimal|histogram|myers}. The default is the Myers diff algorithm, which runs in a theoretical O(ND) time and space, where N=input length and D=edit distance. Its expected runtime is O(N+D²). Not terrible, but the runtime can be badly magnified in large repos.

git add

Adds your working tree to staging area, gotta go fast O(n).

Specifying path git add <path>/* instead of git add --all is obviously faster.

git commit

Like git add, commit is supposed to be fast, but can get bogged down when your repo has a formatter for 5 languages, 2 type-checkers, and sanitization scripts bundled together into pre-commit-hook bloatware. O(∞ⁿ)

If git commit is acting up, you can also run git commit -n to skip commit hooks.

git push/pull

Depends on how your ISP is feeling. Pull also does diffing when attempting to rebase/merge based on your preferred strategy.

git rebase/merge

Rebase and merge have the same-ish effect, and are written similarly. Merge strategy options: --strategy={ort|resolve|recursive|octopus|ours|subtree}. The default merge strategy is ort (Ostensibly Recursive’s Twin) when pulling one branch, and octopus when dealing with 2+ heads. Note ort superseded the old default recursive method in Q3 2021. Under the hood, ort and recursive also call git diff with the default Myers diffing algorithm, which is why it can be slow too.

tl;dr, any operation that requires reading or writing your index will perform a FULL read or write to your index, regardless of the number of files you actually changed.

Sometimes the staging area/index is called the cache.

Stats, for fun

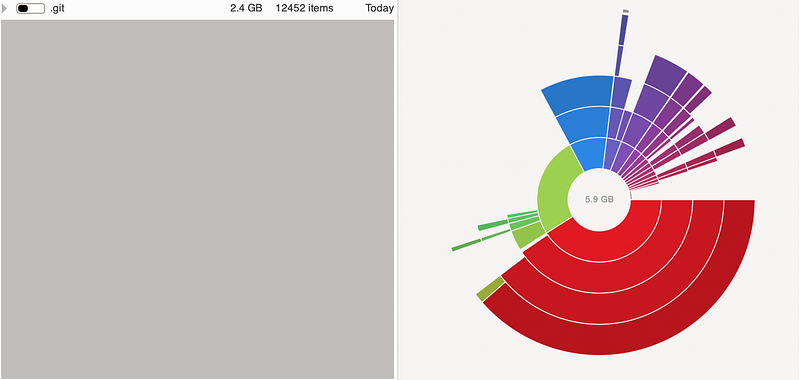

An example monorepo:

- Typical active repo size: 5.9GB (after installation)

- Fresh clone repo size: 3.0GB

.gitsize (consistent): 2.4GB. Unpacking it further reveals a 2.3GB.git/objects/pack, which acts as a database of the repo’s history.

Ok so, how do I git gud? 🧐

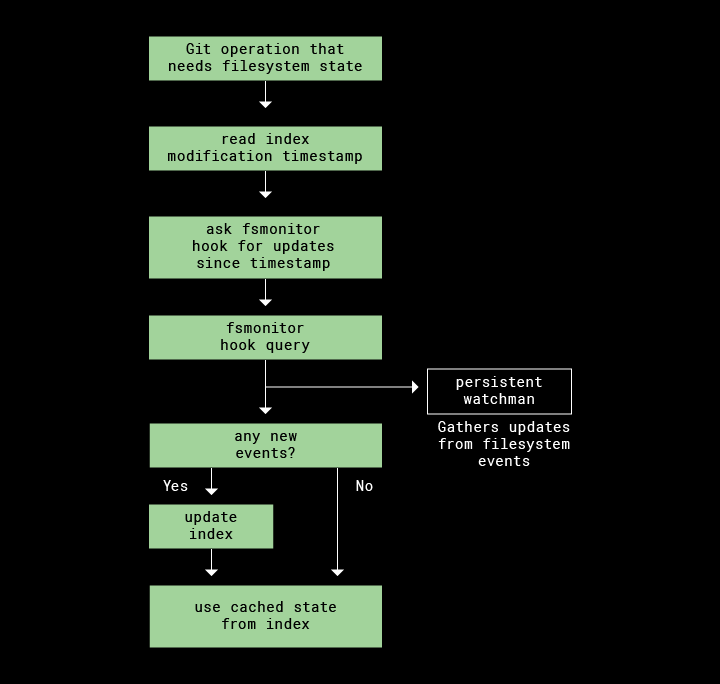

1. Enable fsmonitor-watchman

Enable with the git/hooks/fsmonitor-watchman.sample already in your repo:

cp .git/hooks/fsmonitor-watchman.sample .git/hooks/fsmonitor-watchman

git config core.fsmonitor .git/hooks/fsmonitor-watchman

git update-index --fsmonitorNotes:

- You will need to install watchman

- If you cloned your repo before 3/22/2020 or your git is <v2.26, then you have an outdated

fsmonitor-watchman.samplefile. You can either copy the updated version from the source, or update git thengit initan empty repo to get it. - The rust implementation is faster

2. Use untracked-cache

git update-index --test-untracked-cacheIf it returns OK, run:

git config core.untrackedCache true && git update-index --untracked-cache3. Use split-index

git config core.splitIndex true && git update-index --split-index4. Increase vnode cache size

Default kernel vnodes size is kern.maxvnodes: 263168 (257 * 1024). To increase for your session:

sudo sysctl kern.maxvnodes=$((512*1024))This setting will reset on reboot. To set permanently:

echo kern.maxvnodes=$((512*1024)) | sudo tee -a /etc/sysctl.conf5. Use git status -uno

git status -unoWarning:

-unowill not show untracked files, meaning newly created files will not show up.

6. Incorporate git gc into your workflow

In increasingly aggressive order:

git prune

git gc

git gc --aggressive

git gc --aggressive --prune=now7. Automatically delete old branches

git-delete-squashed is a tool that deletes all of your git branches that have been “squash-merged” into master. Useful if you work on a project that squashes branches into master.

8. Manually delete old branches

# Delete remote and local branch

git push -d <remote_name> <branchname>

git branch -d <branchname>

# Usually the remote name is origin

git push -d origin <branch_name>

# Delete local branch (force)

git branch -D <branch_name>9. Switch to Linux

5–10x faster according to the Dropbox article.

How much faster? 🚀

Results of git status tested using hyperfine with 3 warmup operations and min 30 runs on a basic bash terminal with no plugins.

Test setup:

- Clean repo, 3.0GB

- 2019 16” MacBook Pro (Intel chip, likely lowest configuration)

- IntelliJ, Slack, and Chrome running in the background

0. Control git status:

Time (mean ± σ): 1.487 s ± 0.045 s [User: 324.1 ms, System: 1470.8 ms]

Range (min … max): 1.408 s … 1.587 s 30 runs1. fsmonitor-watchman (9.28% faster):

Perl (6.99%):

Time (mean ± σ): 1.383 s ± 0.061 s [User: 293.8 ms, System: 976.0 ms]

Range (min … max): 1.326 s … 1.645 s 30 runsRust (9.28%):

Time (mean ± σ): 1.349 s ± 0.036 s [User: 275.2 ms, System: 968.9 ms]

Range (min … max): 1.309 s … 1.457 s 30 runs2. Untracked cache (5.85% faster):

Time (mean ± σ): 1.400 s ± 0.042 s [User: 311.9 ms, System: 1414.0 ms]

Range (min … max): 1.340 s … 1.527 s 30 runs3. Split-index (5.98% faster):

Time (mean ± σ): 1.398 s ± 0.072 s [User: 305.8 ms, System: 1404.7 ms]

Range (min … max): 1.323 s … 1.666 s 30 runs4. Increase vnode cache size (2.96% faster):

Time (mean ± σ): 1.443 s ± 0.069 s [User: 316.3 ms, System: 1439.3 ms]

Range (min … max): 1.315 s … 1.562 s 30 runs5. git status -uno (96.1% faster):

Time (mean ± σ): 57.1 ms ± 1.0 ms [User: 49.0 ms, System: 431.7 ms]

Range (min … max): 55.2 ms … 59.5 ms 50 runs1–4. All combined (86.14% faster):

Time (mean ± σ): 206.1 ms ± 100.0 ms [User: 126.9 ms, System: 43.4 ms]

Range (min … max): 181.4 ms … 735.3 ms 30 runsI stepped away and watched an episode of Naruto between the last test and this one, so something weird might have happened here. Not sure if I can trust this data point tbh.

Closing Thoughts

This was a private note that I wrote and tested around May 2021. Since then, I no longer work on the repo, nor do I follow the current state of monorepos. Perhaps there is better version control tooling, especially if dev environments are shifting towards cloud infra such as GitHub Codespaces where machine capability is no longer an issue.

Yes, I have worked with FB’s Mercurial and Salesforce’s Perforce, and I didn’t really have much issue with either. I choose to believe that the engineers there already yoked them to their limits. This article is more or less for startups and companies that have settled on git early on and have not changed version control or repo structure.

Some other improvements that come to mind are enabling this in CI/CD if you are using version control to diff in your pipeline for whatever reason. You can also include these improvements out of the box for onboarding eng, with a script that automates these suggestions. If you have a centrally managed distro of dev tooling, you can also update all your dev machines with this.